The Global Philanthropy Environment Index “Balkan Countries” region includes Croatia and the countries of the Western Balkans: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia. All of these ecnomies are also part of the United Nations Southern Europe Region. The region is a complex mosaic of several ethnic groups and languages, combining large proportions of Christian Orthodox and Muslim populations, together with other minor religious representations (Roman Catholic and Protestants). The countries with majority Muslim populations are Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Albania.

View the full Balkan Countries region reportBalkan Countries

The region is no stranger to religious/ethnic conflicts. Past conflicts between Muslims, Roman Catholics, and Orthodox Christians linger below a surface of fragile peace, and new threats to inter-ethnic relations are always present. In 2016, Conflict Barometer reported conflicts between the opposition and the government in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM), violent protests in Kosovo by the opposition parties, and tensions in BiH, when the Serbian entity decided to hold a referendum over its day of independence (Bosnian Serbs/Republic of Srpska).

The levels of educational attainment in countries in the region are diverse. There are countries with around 20 percent of their population age 25+ at least completing tertiary education such as Croatia, Montenegro, and Serbia. There are also countries like Albania and BiH where less than 15 percent of the adult population has tertiary education completed. Nevertheless, Albania together with Croatia and Montenegro are the countries with the highest percentage of population with at least some secondary education.

Being a region that has seen several wars in the recent past, the Balkan countries have made progress toward transitioning to democratic societies and modernizing their economic infrastructure, as reported by the Bertelesmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (2016). However, these are still countries with defective democracies and some with rather functioning economies, where the progress made in key freedoms, rule of law, and democratic governance are not yet sustainable or irreversible.

The Syrian refugee crisis has affected the countries in the region and the dynamics of their relations with European countries. The most affected countries in the region are Macedonia, Croatia, and Serbia, three bridge countries that became the route of refugee waves mainly toward Germany between 2014 and 2016.

Even after Europe’s closure of the corridor through the Balkans in March 2016, narrower flows of migrants still pass through Serbia (UNHCR, 2018), and because of the strict control imposed to the country’s northern borders, many refugees remain in the country for longer periods. This has led to a “280 percent increase in the number of refugees present in the country between March 2016 and February 2017.” (Serbia International Rescue Committee, 2017.) In the process, Balkan countries have become indispensable partners to control the inflow of refugees and promote stability in the region.

Of the seven countries, only Croatia is a member of the European Union (EU); however, the rest of these countries are either confirmed as candidates for future membership (Macedonia, Montenegro, Albania, and Serbia), or considered potential candidates for membership (Kosovo and BiH). The accession criteria to join the EU requires a functioning market economy and competitive capacity, stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law and human rights, respect for and protection of minorities, and administrative and institutional capacity to implement the common rights and obligations of EU member states.

Kosovo is the last in the queue to join since EU states Spain, Cyprus, Romania, Greece, and Slovakia do not recognize Kosovo’s independence from Serbia in 2008. However, Kosovo has been taking steps toward joining the European Union by signing the Stabilization and Association Agreement (SAA) with the EU and continuing conversations to reach important agreements for normalizing the relations between Kosovo and Serbia. Bosnia and Herzegovina is already part of the SAA with the EU and formally applied for EU membership in February 2016.

The prospect of accession has represented a significant catalyst for reform in the Balkan countries, while receiving technical and financial support for the implementation of reforms. Experts of the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group (BiEPAG) consider that the EU’s ability to export democracy through its enlargement policy is failing to live up to its promise to deliver democracy to those countries engaged in the process of joining the Union, and risks of autocratic regimes are rising in the region. Additionally, the slowdown of the EU Enlargement process has allowed other countries like Turkey, Russia, and the Gulf States to intensify their presence in the Western Balkans with a mixed impact on the region.

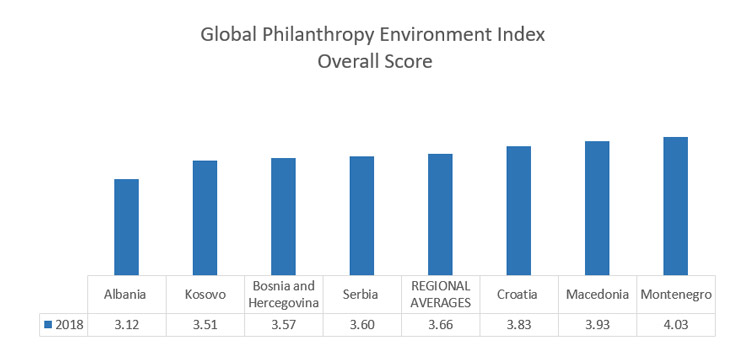

In a region with the backdrop of variable levels of political and economic stability and a civil society sector still oriented toward foreign donations as the primary source of revenue, there is great potential for the emergence and further development of the nascent domestic philanthropy ecosystem in each country.

However, there is an imbalanced legal and regulatory framework on paper and an inconsistent application of even the most progressive frameworks for philanthropy organizations in practice. With growing corporate and individual philanthropy in each country over the past several years, the importance of philanthropy organizations advocating for improved frameworks and their implementation has begun to rise on the prioritization of these organizations’ advocacy agendas.

While philanthropy organizations are generally free throughout the region to form and function with little restriction from the government, except to ensure that anti-constitutional actions or overtly political purposes are not a part of a nonprofit’s intended purpose, the test of whether philanthropic freedom really functions is in how giving and receiving is actually regulated and/or fostered.

While several countries of the region have laws and regulations on the books for providing corporate and/or individual tax exemptions for giving, and some countries even have a developed public benefit designation freeing those philanthropy organizations from paying the VAT tax, in practice these frameworks are cumbersome to navigate, time-consuming to realize, and confusing for all but the most experienced philanthropy stakeholders.

The steady and incremental growth of domestic philanthropy then can not be attributed to the existence or application of improved tax treatments, but rather as a result of the efforts of philanthropy organizations to conduct improved outreach among their individual and corporate donor pools and of an increased awareness among companies on being good corporate citizens.

As such, while philanthropic freedom broadly exists, as philanthropy organizations increasingly orient themselves to domestic sources of philanthropic flows, the demand for an improved enabling environment will increase and countries within this region will be expected to see improvements in their overall ranking on philanthropic freedoms.