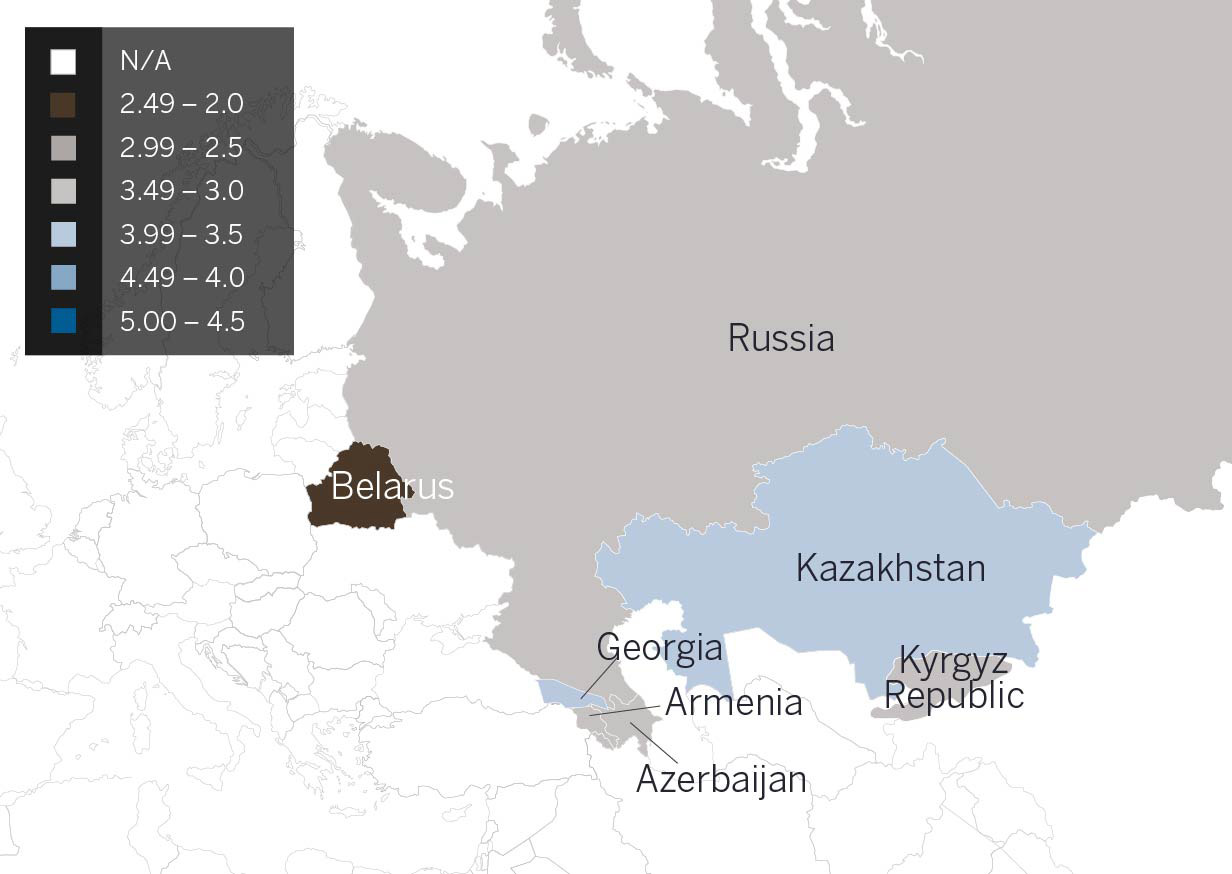

The IPF Central Asia & South Caucasus region includes six of the countries that were part of the Soviet Union before its disintegration in late 1991. These countries are the Republic of Armenia, the Republic of Azerbaijan, The Republic of Belarus, the Republic of Georgia, the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and the Russian Federation. Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan are in the South Caucasus region.

View the full Central Asia & South Caucasus region reportCentral Asia & South Caucasus

The Central Asia and South Caucasus region for the Global Philanthropy Environment Index includes seven of the countries that were part of the Soviet Union before its disintegration in late 1991. These countries are Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Russia.

The region has untapped abundant energy resource reserves and a strategic location that increases the interest of the world’s most powerful economies besides Russia, such as China, and the United States. This has increased the awareness of Russia to prevent the spreading of external major powers on the region, creating a competitive arena where each of these countries tries to influence Central Asian economies and internal politics (Oliphant, 2013). However, Russia maintains its position as a key player in the region.

Several countries in Central Asia still maintain strong ties with Russia and have large proportions of Russian populations, which have left a cultural mark in their countries (Sucu, 2017). There are also important economic links and Russian investments, as well as intergovernmental alliances like the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) led by Russia, and currently including Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

The CSTO’s main task is to coordinate and deepen military-political formation of multilateral structures and mechanism of cooperation to provide national security of Member-States. Meanwhile, China is advancing efforts to open trade routes through infrastructure development in Central Asia, the Caucasus, Iran, Turkey, Russia and Europe—the Silk Road Economic Belt—aimed at reducing physical, technical, and political barriers to trade and expand China’s economic influence over the region (International Crisis Group, 2017).

The countries in this region also have different socio-economic levels. In the Caucasian sub-region, Azerbaijan is the most prosperous state with oil and natural gas exports, while Kazakhstan, with extensive gas and oil reserves is the most prosperous of the countries in Central Asia. After gaining independence, Kazakhstan has emerged as a dominant state in Central Asia, both economically and demographically, and was one of the main promoters of the current Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), officially constituted in 2014, but with precedents in economic treaties that date back to 1995 with the Treaty on the Customs Union.

The EAEU is an international organization for regional economic integration that provides for free movement of goods, services, capital, and labor between Member-States (Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Russia, and most recently Armenia). Although many economies in the region struggled, especially Russia, Belarus, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, in 2017 (USAID, 2017), the Asian Development Bank reported economic growth over 3 percent in the Central Asian region thanks to the moderately rising oil prices.

This growth came with high inflationary pressures especially in Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan. Remittances from Russia and Kazakhstan are also likely to increase, boosting the economy of remittance-receiving economies like the Kyrgyz Republic and Armenia. The current economic recovery of the region is viewed as a window of opportunity to secure higher and more inclusive growth (International Monetary Fund, 2017).

The region presents a rich mixture of ethnicities, some of them within the same country, such is the case of Azerbaijan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Russia. Ethnic tensions are always present in the region such as the clashes between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in the Kyrgyz Republic.

In terms of educational levels, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics reports almost 100 percent literacy rates in the region with an estimated mean of years of schooling of 11.7 years in 2015. However, the educational levels vary from one country to another. In 2015 the gross enrollment ratio in tertiary education was higher in Belarus (87.9 percent) and Russia (80.3 percent), and significantly lower in Kyrgyz Republic (47 percent), Kazakhstan (46 percent), Armenia (44.3 percent), Georgia (43 percent), and Azerbaijan (25 percent).

Politically, all newly created nations in the region have elected presidents several times since 1991, but not all the elections have been considered free and fair. In several countries, presidents have been re-elected through elections that have been considered means to consolidate dictatorships. The Fragile State Index 2017 places all countries in the region in fragile state in relation to “Legitimacy of the State,” an indicator that considers factors related to corruption and lack of representativeness in government.

Besides, according to CIVICUS (2016) several countries in the region—Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Russia—present challenges to human right organizations that face denial of the basic right of association and freedom of expression. In general, the civil society in these countries evolves alongside the political and economic processes in the post USSR period. Georgia, has expressed its desire to become member of the European Union, and both have continued working towards a further deepening of Georgia's political association and economic integration with the EU.

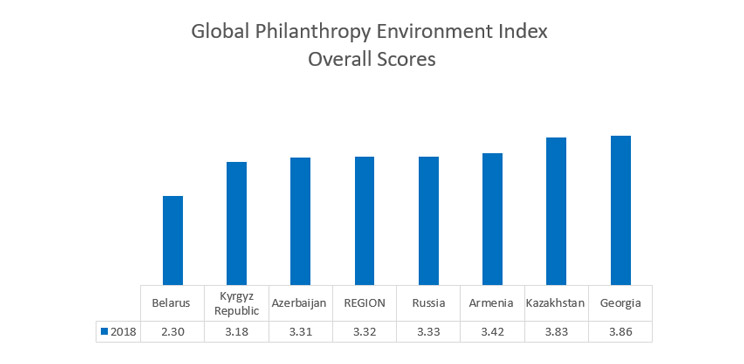

In most countries in the region of Central Asia and South Caucasus, the philanthropic sector is still relatively new, weak and highly dependent on government grants and/or external donors. Although the size of the sector has increased significantly since 1991, there are significant differences among countries.

The different levels of development are sometimes related to the economic (like in Belarus) and regulatory conditions in each country, or tied to specific events. Several countries show the presence of an unfavorable legal environment that does not respond to the needs of the philanthropic sector (for example barriers to freely exercise the right to freedom of association), leading to a poorly institutionalized sector with low levels of professionalization, lack of capacity for effective management, public relations and funding skills, and high levels of informal philanthropic activity.

In recent years, some countries have created more restrictive conditions for the development of a sector already highly dependent on foreign funding, for example labeling foreign-funded philanthropic organizations as foreign agents, as in Russia. Only in Georgia do organizations benefit from a favorable legal and regulatory environment and are able to function without government interference.

Some countries in this region maintain limited to moderately flexible tax incentives that support charitable programs and activities rather than charity organizations, while others offer tax incentives only to certain kind of donors. The limitations on the incentives to donate are observable not only in the percentage of taxable income but also in the potentially low effect of these incentives on the growth of philanthropy due to a not sufficiently developed philanthropic culture in the region.

In general, policies in the region seem to be more restrictive for receiving than for sending donations, and several countries are basically recipients and rarely donors. In most of the countries in the region, philanthropic organizations operate under growing political control, high levels of scrutiny, and reduced government and international funding to certain types of independent philanthropic organizations.

Although civil society in the region is familiar with the concept of giving as part of traditional or religious practices, civil participation as part of the solution to social problems is slowly developing. Simultaneously, in many of these countries corporate philanthropy is evolving, and middle class professionals are becoming more engaged in philanthropic activities. This hints that there is potential for the growth of philanthropy.