Political corruption, social inequality and informal employment are three of the most important challenges and obstacles for sustainable development in Latin American societies. Economic and social studies made by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) show that Latin America is a region with “sharp structural heterogeneity” in terms of structures of production, exercise of rights and the development of capacities, all of which are largely responsible for the high levels of social inequalities.

View the full Latin America region reportLatin America

On average, the 2015 GINI coefficient (ranging from 0, complete equality, to 1, complete inequality) for the region as a whole was 0.469. Venezuela, Argentina, and Uruguay were significantly over this level, meaning these nations experience greater inequlity when compared with other Latin American economies.

Inequality disproportionately affects women, especially women living in rural areas. In general, there is an overrepresentation of women ages 20 to 59 in the poorest income segments of the population, up 40 percent compared to men. This trend is the result of women receiving lower wages, in addition to the fact that they are often operating as heads of single-parent households (ECLAC, 2016).

Educational attainment levels are also uneven. Data from the UN Human Development Index reveals that the percentage of population with at least some secondary education (ages 25 and older) between 2005 and 2015 is highest in Chile (75.5 percent), one of the two Latin American OECD countries together with Mexico. Venezuela and Argentina follow Chile with 68.9 and 62.4 percent respectively, and Ecuador has the lowest (48.8 percent) proportion of population with at least secondary education.

Data from Venezuela has undoubtedly changed in the last few years as the country has become a global exporter of highly qualified professionals fleeing from the economic crisis and deteriorated democracy. Venezuelan emigration is made up of people who have many years of experience, college degrees (90 percent), master’s degrees (40 percent) or doctoral degrees (10 percent). (Paez, 2017)

Some countries in the Latin American region share levels of political violence and instability connected with drug trafficking, organized crime, abusive use of political powers by government and selected groups, fragility of mechanisms of accountability, and high levels of corruption. Historically, domestic conflicts in the form of social and political revolutions leading to violence have been connected to unequal patterns of distribution of wealth, lack of political rights, and social exclusion.

Politically, Latin America is advancing in a myriad of directions that respond to the continued efforts by internal and external political actors to shape the democracies in the region. All countries in the region are, at the moment, representative democracies, with dissimilar levels of political freedom.

Freedom in the World 2017 catalogues Venezuela as “Not Free,” and Bolivia, Colombia and Ecuador as “Partly Free.” The rest of the countries in the region guarantee acceptable levels of political rights. However, these countries have not avoided multiple manifestations of violence including unjustified arrests, attacks to freedom of speech, and indiscriminate repression and use of force.

The study published by Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (2016) about Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela, talks about the multiplication of laws, bills, regulations, and judicial interpretations aimed at limiting political rights and criminalizing social protests in Latin America in the last 10 years.

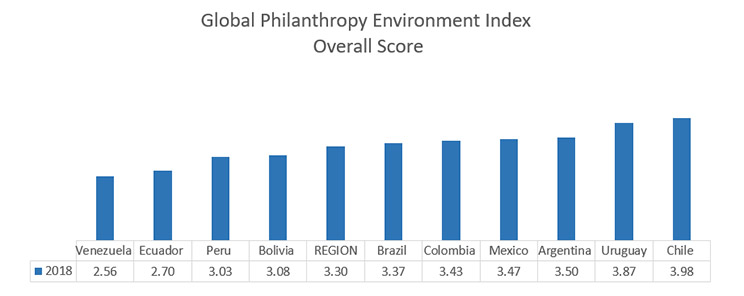

For instance, new “Anti-terrorism” laws or reforms suspend procedural guarantees or establish broad criminal categories, enabling their use to criminalize conflicts, like in Brazil (2016) and Venezuela (2012). However, recent changes in the political regimes in Ecuador, Argentina, and Brazil may lead to regaining political rights for civil society organizations. In October 2017, the president of Ecuador repealed Decrees 16 and 739, previously used to exercise control and dissolve several civil society organizations. Nevertheless, Ecuador ranks near the bottom of our Global Philanthropy Environment Index.

Amidst these multiple challenges, the region has shown signs of economic recovery and shifts to stronger democracies accompanied with non-traditional levels of voluntary intraregional migration in the last few years. Economically, the region shows signs of fragile recovery after five years of deceleration and one of recession, especially in Argentina and Brazil (World Bank, 2017). However, Bloomberg’s Misery Index, which sums inflation and unemployment outlooks for 66 economies, ranks Venezuela as the world’s most miserable economy four years in a row (Bloomberg, 2018).

Venezuela’s economy is collapsing, while emigration rates increase. According to the World Bank, remittance inflows to Venezuela have reached a maximum point of US$289 million in October 2017, as migrants attempt to help families survive the crisis, almost 70 percent higher than 2015.

The Latin American region has had a rich history of philanthropy since the conquistadores established themselves in the New World. From 1492 onward, they instigated similar administrative functions in New World colonies that were in force at the time in Spain, including deference to the Catholic Church in the area of public welfare. For three and a half centuries of Spanish and Portuguese rule in the Americas, philanthropy was instilled by the Church and the crown, and a rich tradition of philanthropy imbued the region.

After the wave of independence in the 19th century, secular philanthropy evolved differently in the hearts and politics of each nation, and continues to do so, explaining the vast disparity in today’s country scores although derived from a singular history.

This report includes all sovereign countries of South America, except Paraguay, Guyana, and Suriname. It does not represent territories and dependencies of Central America, but it does include the North American country of Mexico. All told, representative countries herein contain approximately 86 percent of the population of the entire Latin American region.

A wide range of philanthropic policies and enabling environments span the region. Very favorable philanthropic climates exist in Chile and Uruguay, with minimal regulation and oversight, high levels of freedom to form philanthropic organizations (POs) in all subsectors, and government-driven complementary contracts. Such climates also cultivate a tradition of philanthropic giving and volunteering.

A larger portion of the countries in this region experience somewhat restrictive philanthropic climates, including nations such as Argentina, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico. They have high levels of volunteerism and rich cultures of giving, but with some burdensome regulations regarding PO formulation, tax treatment, oversight, and cross-border transactions. These put a damper on civil society institutionalization, and so a significant informal philanthropic sector exists in these countries.

Brazil, for example, does not permit tax-immune organizations to donate outside its borders, but informal groups circumvent the law. Widespread corruption and lack of trust in the sector reduce effectiveness of individual donations to POs, despite increased anti-laundering and transparency laws. To their credit, however, these governments are generally encouraging of solutions stemming from the third sector, and even strategically partnering with it. Additionally, corporate social responsibility, likely driven by Millennials, is making great strides in these countries.

Finally, a couple of socialist-leaning nations have highly unfavorable philanthropic environments, namely Ecuador and Venezuela. POs are generally considered adversarial. Human rights organizations are not permitted; involuntary dissolution of POs does not honor due process and recourse is limited; PO registration authorities are corrupt and inconsistent; and cross-border transactions are controlled or taxed.

Civil society leaders are even imprisoned or otherwise punished. At the end of 2014, USAID was forced to leave Ecuador by a presidential decree. The situation is worse in Venezuela, as even philanthropic activities in non-political areas, such as health and food, have been under threat or outright blocked. The philanthropic outlook in these two countries is bleak, although socio-cultural values and practices remain strong.