Most of the countries in the region recently celebrated 50 years of independence from colonial rule. Scholars note that the new philanthropic landscape has the “distinct character of African agency, energy and engagement” (Aina & Moyo, 2013). The emerging middle class in many African cities holds promise for the immediate future of philanthropy. Yet profound disparities remain between the urban and rural populations within countries.

The most recent data provided by UNESCO (2015) shows that of all regions, Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rates of population with no schooling and the greatest gap in girls’ education. A recent report shows that while primary attainment rates have improved, in the poorest countries the gap between the average and poorest households increased between 2003 and 2013 (UNESCO, 2015).

Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are experiencing economic growth at a very slow pace. According to the International Monetary Fund (2017), 2016 marked the region’s worst performance in more than two decades, but growth started to recover in 2017 with fading drought in several geographic areas and modest improvements in trade.

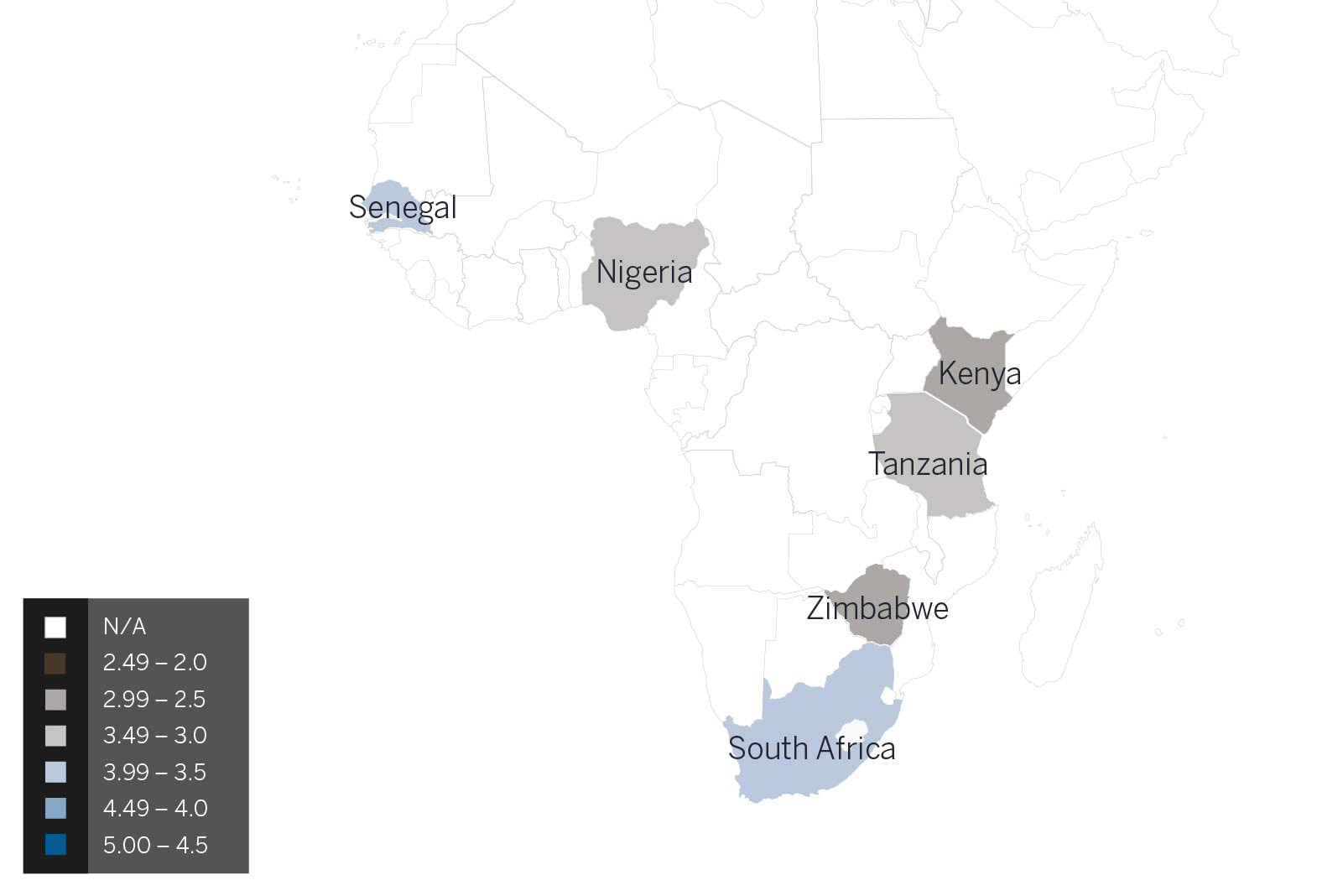

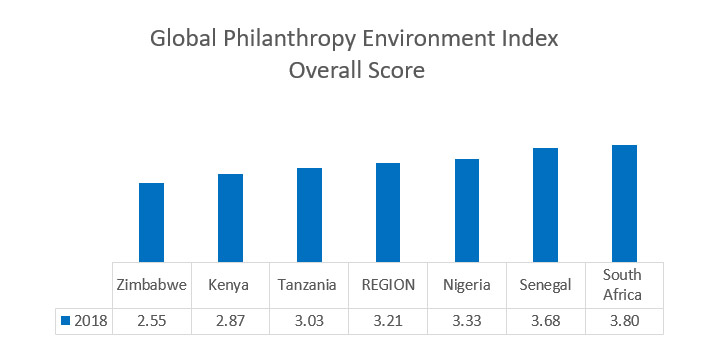

Regardless, growth rates in 2017 and the expected growth rates in 2018 are considered insufficient to achieve poverty reduction in the region (World Bank, 2017). However, each country in the study represents unique opportunities and threats for the development of the philanthropic sector in the region. For example, Kenya is a major hub for communications and logistics, with one of the fastest growing economies in Sub-Saharan Africa.

With nearly half of the population of West Africa, Nigeria has one of the largest populations of youth in the world. Likewise, Tanzania faces a high population growth rate, with 800,000 youth entering the job market every year. Despite economic growth, nearly half of the population lives on less than US$1.90 per day, with many of those in poverty living in rural areas.

The economic growth is difficult to perceive in these areas, especially where agricultural practices are unsustainable. Though Senegal has not developed the financial prosperity of others in the continent, it has enjoyed one of the most stable democracies in Africa since the end of the colonial period. Finally, South Africa remains, perhaps, the primary economic leader for the continent. Yet it is a dual economy, with some of the world’s highest rates of inequality (World Bank, 2016).

Illegal financial flows and corruption are two of the greatest and growing issues in Sub-Saharan African economies. The Corruption Perception Index (2016) places Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Nigeria, and Kenya among the countries with high corruption rankings (over 115 out of 176), despite efforts in some countries like Kenya to adopt anti-corruption measures, including passing a law on the right to information.

Senegal and South Africa are better positioned. The Index reflects the impacts of corruption by aggregating 13 different data sources that provide perceptions of business people and country experts of the level of corruption in the public sector, but it does not reflect illicit financial flows.

Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a nonprofit research and advisory organization working to curtail illicit financial flows, estimates that developed countries and their institutions “actively facilitate—and reap enormous profits from—the theft of massive amounts of money from developing countries” and that “illicit financial outflows from developing countries ultimately end up in banks in developed countries like the United States and United Kingdom, as well as in tax havens like Switzerland, the British Virgin Islands, or Singapore.” (Spanjers & Salomon, 2017)

OECD (2018) reports that West Africa is a transit zone for cocaine from Latin America destined for European markets. The GFI report published in 2017 about illicit financial flows. Although African economies have made significant efforts to comply with international regulations and institutions the enabling conditions persist that allow individuals to undertake illicit activities with relative impunity. Among them, the high levels of corruption and the limited access to the banking system for many ordinary people creates informal systems of financial transactions, such as the hawala system for cross-border transactions (OECD, 2018).

In addition, many of the laws intended to bolster the fight against financial crimes can negatively impact the abilities of philanthropic organizations to send and receive donations across borders.

According to the Freedom in the World 2018 report (Freedom House, 2018), several governments in the region, including Zimbabwe, Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa, use repressive tools to strengthen their own political power. In terms of political rights and civil liberties, Senegal and South Africa were designated free, while Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania were ranked as partly-free countries in 2017.

Zimbabwe was scored as a not-free country last year since President Mugabe was compelled to resign under military pressure. As the Mugabe regime oppressed philanthropic organizations and subdued democratic forces, the following years might bring positive changes to the Zimbabwean philanthropic sector.