Unknown Region

Region details unavailible.

- 5.0–4.5

- 4.49–4.0

- 3.99–3.5

- 3.49–3.0

- 2.99–2.5

- 2.49–2.0

- None (base)

Eastern & Southern Europe

The Eastern and Southern Europe region of the Global Philanthropy Environment Index is both geographically and religiously diverse, and includes economies in Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovak Republic, and Ukraine) and Southern Europe (Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain).

Nine countries are members of the European Union: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, and Spain; and Ukraine is one of the priority partners of the European Union. The most represented religions are Roman Catholic and Orthodox; but the common Christian values and practices have contributed to create similar philanthropic traditions across the region.

View the full Eastern & Southern Europe region reportMost economies in the region—Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovak Republic, and Ukraine—had communist regimes until 1989-91. However, while in Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic and Slovak Republic) underground philanthropic organizations were catalysts of the political transition towards democracy, in Bulgaria (and also in Ukraine) the authoritarian communist regimes completely suppressed philanthropic activities (Vandor, Traxler, Millner, & Meyer, 2017), hindering the development of philanthropy. After the transition period, both individual and institutional philanthropy have been rebuilt in Eastern Europe, influencing the current philanthropic landscape.

In general, the educational attainment of the countries in the region is slightly below the OECD average (42.6 percent) (OECD, 2017). Except for Poland where the proportion of 25-34 year-olds with tertiary education reaches 43.5 percent, the rest of the countries in the region are below average with Spain and Greece in similar position (41 percent), and Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Portugal, and Slovak Republic with proportions between 30 and 35 percent (OECD, 2017; European Commission, 2015).

Italy has the lowest level of educational attainment in the region. The proportion of 25-34 year-olds with tertiary education in Italy is only 25.6 percent, having the second lowest level of tertiary education among OECD countries (OECD, 2017).

The region has faced political and economic challenges, including the 2008 economic crisis, the 2009 European sovereign debt crisis, the 2014 Ukrainian refugee crisis, and the effects of the Syrian refugee crisis. While the 2008 economic crisis affected almost all countries in the region and forced them to initiate austerity measures, the 2009 European sovereign debt crisis had a long-standing and severe impact on Greece, Spain, and Portugal.

As consequence, the countries affected by the 2009 European sovereign debt crisis were unable to refinance their government debt or bail out over-indebted banks without receiving financial support package from third parties, including the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund (De Santis, 2012). While Portugal and Spain were able to successfully exit due to the European Union and the European Union/ International Monetary Fund bailout mechanisms, Greece is still in the process of economic recovery.

Recently Italy, Portugal, and Spain face a potential banking crisis due to the increasing levels of nonperforming bank loans. In Italy, the level of nonperforming bank loans has exceeded US $400 billion, which is 18 percent of all bank loans in the country. This comes at a time when the European Union has made bail-out regulations stricter in terms of recapitalizing commercial banks and financial institutions in the Eurozone (Micallef, n.d.).

Besides the economic difficulties, the region has faced two refugee crises. In 2014, the Euromaiden Revolution and the subsequent armed conflict in some eastern and southern regions of Ukraine led to the Ukrainian refugee crisis, where millions of Ukrainians became internally displaced persons. In 2015, millions migrants and refugees crossed into Europe from Syria, resulting in one of the largest refugee flows since World War II. As a consequence of the Syrian refugee crisis, three border countries of both the European Union and the Schengen Area—Greece, Italy, and Hungary—have been impacted by the inflow of refugees.

Simultaneously, anti-immigrant sentiment has been increasing in several countries, especially in countries of the Visegrad group: Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and the Slovak Republic (The Economist, 2017).

The aftermath of the economic crisis, such as the increased level of unemployment, government austerities, and the current refugee crises have led to internal domestic political tensions in the countries of the region. Political instability was reported from Bulgaria, Greece, and Ukraine, while political tension between the government and philanthropic organizations have been amplified in Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and the Slovak Republic recently.

The hostile political environment, the decreasing level of governmental funding for philanthropic organizations, and the increasing demand for charitable services put the philanthropic sector in a challenging situation.

Ten ecnomies representing Eastern and Southern Europe differ in a number of aspects. However, during the period under review, they have shared some significant similar experiences, too. These similarities could be labeled as “political and economic challenges.” The countries have witnessed the economic crisis, the sovereign debt crisis, and the refugee crisis. Consequently, philanthropic organizations today face another crisis in some countries; a crisis of legitimacy, which could become an alarming trend, especially in Eastern Europe.

In this difficult period, several development themes in the region can be identified. Firstly, there is an increasing demand for social services (basic needs) and, on the other hand, the limited ability or willingness of national governments to meet these needs. The next line represents a rapidly polarizing society as a result of the above mentioned crises.

Philanthropic organizations can also face more restrictive policy toward the sector; an example is the constraints associated with the creation and registration of these organizations. On the other hand, open "hostility" from the government is yet to really be seen. Although, the latest developments in Hungary may contradict this claim.

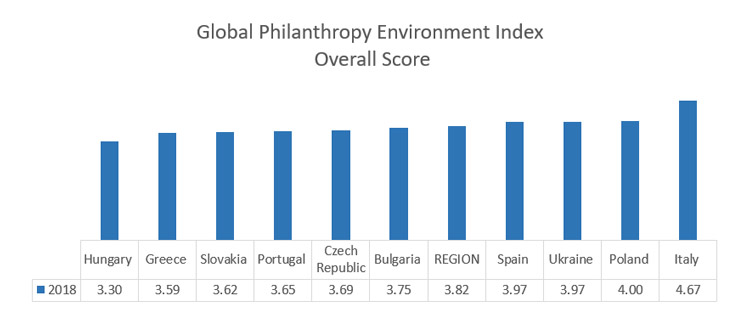

Although expressing the country position through the “scores” might be slightly tricky, the scores can give us a fair picture of overall country similarities, differences and trends. Generally, every country indicates some difficulties, obstacles or dilemmas.

Italy seems to be the only exemption as its particular scores never drop under 4.5. Italy’s performance can be explained by a democratic tradition and long-term experience with the nonprofit sector in the country. Moreover, unlike in some other countries, Italy can benefit from the new provisions introduced by the first Italian Third Sector Act, bringing crucial changes into the nonprofit organizations’ legal framework.

While, at least in the case of legislative conditions concerning the organizational formation and government interference, there are no extreme deviations between economies in the region, the fields of taxation, cross-border donations and socio-cultural conditions indicate rather significant differences and in some cases also obstacles and inconveniences for the philanthropic organizations (that is particularly true in Greece and Portugal). Finally, fragile partnerships between the philanthropic and public sectors should be mentioned.

In this context, the irreplaceable and, perhaps, most important role of philanthropic organizations and civil society can be observed. As can be seen in individual national reports, its significance lies not only in providing social services for citizens, but also in the activities supporting, in the broadest sense, the cohesion and functionality of the whole society.