Unknown Region

Region details unavailible.

- 5.0–4.5

- 4.49–4.0

- 3.99–3.5

- 3.49–3.0

- 2.99–2.5

- 2.49–2.0

- None (base)

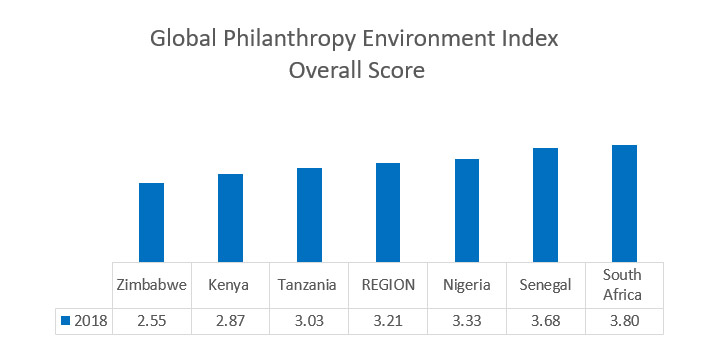

Sub-Saharan Africa

The Sub-Saharan Africa region contains 53 countries with an estimated total population of 1.03 billion (UN Statistics, 2017, World Bank, 2016). Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe account for 36.5 percent of the population.

The region is characterized by multi-ethnic and multi-cultural qualities influenced by different religious beliefs and traditions. According to the Pew Research Center (2015), Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the most religious regions; 62.9 percent of the region’s population identify themselves as Christians, and 30.2 percent as Muslims.

The most represented religion in Kenya, South Africa, and Zimbabwe is Christianity; in Senegal is Islam, and in Nigeria and Tanzania both Christianity and Islam are dominant religions. Nigeria is the second most religious country in the world (Gallup International, 2015).

View the full Sub-Saharan Africa region reportMost of the countries in the region recently celebrated 50 years of independence from colonial rule. Scholars note that the new philanthropic landscape has the “distinct character of African agency, energy and engagement” (Aina & Moyo, 2013). The emerging middle class in many African cities holds promise for the immediate future of philanthropy. Yet profound disparities remain between the urban and rural populations within countries.

The most recent data provided by UNESCO (2015) shows that of all regions, Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rates of population with no schooling and the greatest gap in girls’ education. A recent report shows that while primary attainment rates have improved, in the poorest countries the gap between the average and poorest households increased between 2003 and 2013 (UNESCO, 2015).

Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are experiencing economic growth at a very slow pace. According to the International Monetary Fund (2017), 2016 marked the region’s worst performance in more than two decades, but growth started to recover in 2017 with fading drought in several geographic areas and modest improvements in trade.

Regardless, growth rates in 2017 and the expected growth rates in 2018 are considered insufficient to achieve poverty reduction in the region (World Bank, 2017). However, each country in the study represents unique opportunities and threats for the development of the philanthropic sector in the region. For example, Kenya is a major hub for communications and logistics, with one of the fastest growing economies in Sub-Saharan Africa.

With nearly half of the population of West Africa, Nigeria has one of the largest populations of youth in the world. Likewise, Tanzania faces a high population growth rate, with 800,000 youth entering the job market every year. Despite economic growth, nearly half of the population lives on less than US$1.90 per day, with many of those in poverty living in rural areas.

The economic growth is difficult to perceive in these areas, especially where agricultural practices are unsustainable. Though Senegal has not developed the financial prosperity of others in the continent, it has enjoyed one of the most stable democracies in Africa since the end of the colonial period. Finally, South Africa remains, perhaps, the primary economic leader for the continent. Yet it is a dual economy, with some of the world’s highest rates of inequality (World Bank, 2016).

Illegal financial flows and corruption are two of the greatest and growing issues in Sub-Saharan African economies. The Corruption Perception Index (2016) places Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Nigeria, and Kenya among the countries with high corruption rankings (over 115 out of 176), despite efforts in some countries like Kenya to adopt anti-corruption measures, including passing a law on the right to information.

Senegal and South Africa are better positioned. The Index reflects the impacts of corruption by aggregating 13 different data sources that provide perceptions of business people and country experts of the level of corruption in the public sector, but it does not reflect illicit financial flows.

Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a nonprofit research and advisory organization working to curtail illicit financial flows, estimates that developed countries and their institutions “actively facilitate—and reap enormous profits from—the theft of massive amounts of money from developing countries” and that “illicit financial outflows from developing countries ultimately end up in banks in developed countries like the United States and United Kingdom, as well as in tax havens like Switzerland, the British Virgin Islands, or Singapore.” (Spanjers & Salomon, 2017)

OECD (2018) reports that West Africa is a transit zone for cocaine from Latin America destined for European markets. The GFI report published in 2017 about illicit financial flows. Although African economies have made significant efforts to comply with international regulations and institutions the enabling conditions persist that allow individuals to undertake illicit activities with relative impunity. Among them, the high levels of corruption and the limited access to the banking system for many ordinary people creates informal systems of financial transactions, such as the hawala system for cross-border transactions (OECD, 2018).

In addition, many of the laws intended to bolster the fight against financial crimes can negatively impact the abilities of philanthropic organizations to send and receive donations across borders.

According to the Freedom in the World 2018 report (Freedom House, 2018), several governments in the region, including Zimbabwe, Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa, use repressive tools to strengthen their own political power. In terms of political rights and civil liberties, Senegal and South Africa were designated free, while Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania were ranked as partly-free countries in 2017.

Zimbabwe was scored as a not-free country last year since President Mugabe was compelled to resign under military pressure. As the Mugabe regime oppressed philanthropic organizations and subdued democratic forces, the following years might bring positive changes to the Zimbabwean philanthropic sector.

Philanthropy remains a multi-sided, diverse, and complex terrain with a wide range of dynamics and actors in terms of its intersection with states, societies, communities, civil societies, and businesses in Africa. This complexity and variety have implications for the often diverse, and sometimes conditions of the philanthropic environments found in the region.

Overall, philanthropic organizations’ relationships with the states and governments continue to determine the philanthropic environment in the period under review. These relationships are not uniform, as they depend on contexts and the issues involved. They range from hostility when it comes to issues related to governance, rights, and accountability, to acceptance and accommodation when it comes to the provision of services and humanitarian response.

With regard to other issues such as women’s economic empowerment and climate change, the relationship can be characterized by ambivalence and/or avoidance. So the philanthropic environment, as defined by the indicators used in this review—such as freedom to organize and associate, freedom to give and receive both within and across countries, and constraints that culture and traditions impose on philanthropy—cannot be reduced to simple generalizations that ignore the more complex and diverse contexts and periods.

Another important consideration that can be derived from the review is that, although many African societies have vibrant philanthropic traditions based on religion, such as Islam, Christianity and traditional faiths, the modern forms of philanthropic expression as typified in structured and systematic institutionalized giving are unevenly distributed across countries, regions, and groups. The review, however, shows that new philanthropic institutions owned and established by Africans continue to emerge and grow.

There are also new trends in modes and ways of giving, particularly those driven by new technologies such as the Internet and mobile telephones. These are creating new conversations and orientations around not only philanthropic giving but also the interventions and actions of philanthropic organizations. While new modes of engagement have implications for the philanthropic environment of the region, they have also provoked governmental efforts aimed at creating new regulations and restrictions.

Simultaneously, however, nervous and insecure governments are using aspects of negative global trends such transnational terrorism, money laundering, and trafficking to impose greater controls on what they consider to be unwanted and/or unacceptable expressions of philanthropy. Thus, the space for civil society has been increasingly shrunk by governments in the period under review through hostile or ambivalent actions.

In spite of these trends, the period is not characterized by unmitigated pessimism for the future of the environment for philanthropy. This is because the period saw innovations in organizing and mobilization through social media and other electronic means. It saw the birth of new formal philanthropic organizations by high net worth individuals, communities, and corporations. It also saw the resilience of civil society and philanthropic organizations as their drivers and actors invent new ways of managing difficult human rights and social justice conditions and governments.

The review, in fact, pointed to the inadequacy of a monolithic understanding of the region’s philanthropic environment and the need to avoid generalizing about any particular trend across the continent. The review shows that, although a lot remains to be done to attain a more vibrant philanthropic environment, the outlook is not entirely negative or pessimistic.